The faraway lights of Chamonix fade as vivid crimson floods over the glacier, its tumbling icefalls illuminated like shattered skyscrapers.

My headlamp reflects off polished blue ice and dissipates into a dark void. Steadying myself, I step over a crevasse wide enough to swallow a person, stomping to ensure my ski crampons have a hold on the other side. We make many more delicate moves, like a calculated game of alpine chess as we progress upward, my world confined to the orb of my headlamp. Later on, if all goes as planned, we’ll make our way back down from the summit, the soft snow as our canvas. It is always a delicate dance with the mountain.

What is ski touring? For me, it is a fully immersive moving meditation. It is the inexplicable condensing of complexity and aligning of factors that make an objective come to fruition. It is what has led me to build my life around backcountry skiing—of chasing distant peaks, couloirs and wild views, of consistently humbling and challenging myself, learning, and coming back for more.

Ski touring has unquestionably given me the best memories of my life. If you’re reading this, I’d venture a guess that you’re after that too.

How I Got Into Ski Touring

I was raised about as far from the Alps as you can get culturally, but immersed in ski culture. Growing up in Montana, my dad, a farmer and rancher by summer, ski patroller come winter, started me early. Before I turned two, he put me on my first pair of skis a few inches longer than a wine bottle. These days, I’m on snow for work and play around 120 days per year.

As a ski guide, it’s my job to introduce people to the backcountry. I often meet backcountry-curious riders who ask how they can progress from chairlifts to exploring on their own terms.

If you’re trying to unlock the steps to get out ski touring, I hope that this can serve as a foundational resource, or a map of sorts, to help point you in the right direction.

Two Views on Ski Touring: Europe and North America

I consulted my colleague, mentor and IFMGA guide Eric Larson to help add a European viewpoint based on his decades of guiding extensively in the Alps. Larson has a wealth of experience on snow, as a long-time internationally certified mountain guide, ski patroller, and member of the AMGA instructor team.

Larson started backcountry skiing 31 years ago (which might be longer than I’ve been alive). He’s been ski guiding in Europe since his first trip on the classic Haute Route between Chamonix and Zermatt in 2008, and despite being a consummate professional, he’s still a ski bum at heart. We both work for Mountain Trip, an international guide service primarily operating in the Alaska Range and the San Juan Mountains of Colorado.

We’ve set our sights on providing a comprehensive overview of introductory ski touring, incorporating the differences between Europe and North America.

Some high level differences between ski touring in Europe and North America:

-

- North America has more untouched wilderness for raw exploration, whereas Europe has more pervasive and convenient infrastructure, like trams, huts and detailed guidebooks.

- Europe has much more access to alpine terrain and glaciers, whereas North America features a mix of above and below treeline skiing.

- Often, the Alps have faster and more predictable rescue, and North American backcountry skiers should be more prepared to self-rescue.

- Skiing in Europe is generally cheaper than in North America, and uphill travel is more widely available at ski resorts.

A Brief History of Ski Touring

The roots of modern ski touring can be traced back to the Nordic countries, with records of people sliding around on wooden skis dating to the 1500s. Once exploration picked up in Western Europe and glaciers receded granting access into once impassable valleys, ski touring became the most practical method of winter travel in the mountains. As human influence pervaded the Alps, so did the sport.

Ski touring made its way to North America during the early 1800s, spearheaded by Scandinavian immigrants. In high alpine mining boomtowns of the west, skiing was limited to a handful of intrepid participants, but it began to catch on as people moved higher into the mountains. Many historical accounts describe onlookers mystified by the first backcountry skiers: Norwegian miners making swooping powder turns at 12,000’ and Chamois hunters in the Chamonix valley laying tracks in remote cirques. Skiing eventually evolved from simple utilitarianism into a means of seeking fun and adventure.

When ski areas began to pop up across the eastern United States with the industrial revolution, ski touring declined. Conversely in Europe, as infrastructure grew, ski touring did alongside it. These two histories have developed separately, creating unique interpretations of the sport depending on where you click into your bindings.

What Is Ski Touring? Is It Different Than Backcountry Skiing?

Let’s start by defining our terms. The world of skiing has an extensive and specialized vocabulary that can be confusing to the uninitiated.

I may use the terms “ski touring” and “backcountry skiing” interchangeably, but they have different connotations.

Ski touring is travel uphill on skis with the intent of eventually skiing down. This can be done anywhere, including on controlled resort terrain, and is simply referring to the uphill-capable gear and specific movement.

Note: this article is centered around alpine skiing, a distinct sport from Nordic skiing (which involves primarily horizontal movement without the downhill component, and utilizes entirely different equipment). Do not use Nordic skis for backcountry skiing.

Backcountry skiing

Any skiing that takes place off a resort, outside of the avalanche-mitigated, patrolled and controlled boundaries. You’ll find yourself on a wider array of snow surfaces, from the deep powder of your dreams, to chattery, bulletproof ice, to supremely fun “corn” snow (when the surface-level snow melts to slush to create fast, soft conditions).

Sidecountry skiing

This is skiing in the backcountry, accessed through a gate on a ski resort, and occasionally may not involve going uphill at all. This is generally a distinction only used in North America.

In Europe, it’s on-piste or off-piste

“In Europe, they do not use the terms backcountry or sidecountry. You are skiing either on-piste, or off-piste,” says Larson.

“The only runs on a ski area that are controlled are groomed pistes [meaning runs], or the terrain above them that may cause an avalanche that would threaten people or infrastructure, like restaurants or ski lifts.” In other words, the lines of where “backcountry conditions” may exist are blurrier in Europe. On-piste areas are controlled for risk, whereas off-piste areas are not. Both exist within resort boundaries.

Ski mountaineering

Conversely, ski mountaineering kicks typical backcountry skiing up a few notches: in terms of gear, experience needed, altitude achieved and steepness skied. Ski mountaineers blend all of the elements of ski touring with technical climbing to reach high peaks to then ski or snowboard back down. This discipline requires the use of ropes, ice axes, crampons, rock and ice protection, and climbing gear.

A niche of ski touring, called skimo or ski randonée (also short for, and sometimes called “ski mountaineering,” but very different from the above description), is popular in the Alps and gaining traction in North America. Skimo uses minimalist and ultra-light versions of typical gear, and usually is done as training to tackle endurance races.

Freeskiing

Freeskiing is layering on top of all of this with a fast and intrepid big mountain skiing style—making big arcing turns, hitting cliffs, and interpreting the terrain artistically at high speeds. This is limited to a small selection of elite or professional skiers.

Snowboarders

I should highlight that snowboarders also find themselves in all of this terrain, and whenever I say, “ski,” I mean for that to include riders of all modalities. For uphill and backcountry travel, snowboarders use a tool called a splitboard, which is precisely that: a board that splits apart into two skis for going uphill, and fastens back into a snowboard for slashing your way down.

Why Go Ski Touring?

Backcountry skiing unlocks a level of freedom not possible within the confines of a ski resort. It allows us to interface with nature more intimately with fewer distractions. It forces us to slow down and be fully present in the environment around us. Many of us backcountry skiers can’t put our finger on a single element that compels us, but there’s a long list of factors at play.

Different reasons to go ski touring

While the core reasons are the same, North Americans and Europeans often have different “whys” for taking up the sport. Of course, with anything, all of these stated differences have exceptions; I’m not trying to put anyone in a box.

In the Alps and throughout Europe, ski touring is much more visible, and the lines are blurred between ski touring and resort skiing.

“Most Europeans take to ski touring for the sake of exercise and movement, which is so ingrained in their culture,” says Larson. Many also seek out the views afforded by the extra effort, and the pure pleasure of traveling through the mountains.

In North America, ski touring culture tends to be much more focused on powder seeking, solitude and exploration. Skiers are compelled to find fresh tracks outside of busy ski resorts.

“In the Alps, almost everyone grows up skiing; it’s maybe a more immersive ski culture. The ski areas are mostly all above treeline, so they see ski touring always happening all around them, compared to in North America, we don’t typically see backcountry skiers on a daily basis—it’s not always front of mind. I think the exposure is lower and backcountry skiing is less culturally ingrained in North America in mountain communities,” Larson reasons.

That may be one reason for less adoption in North America. The dangers are certainly another.

Risks of Ski Touring: How to Stay “Safe”

There is no way to talk about backcountry skiing without acknowledging the associated danger. I’d love to tell you that there is a foolproof, “safe” way to do it, but in the mountains, it is impossible to control everything. Rocks fall unexpectedly, avalanches can be unpredictable and storms can arrive at the worst possible moment.

As guides, we avoid ever saying the word “safe.” Safety is an outcome of practicing good risk management, planning and assessment, but you can never make guarantees in the mountains.

Avalanches

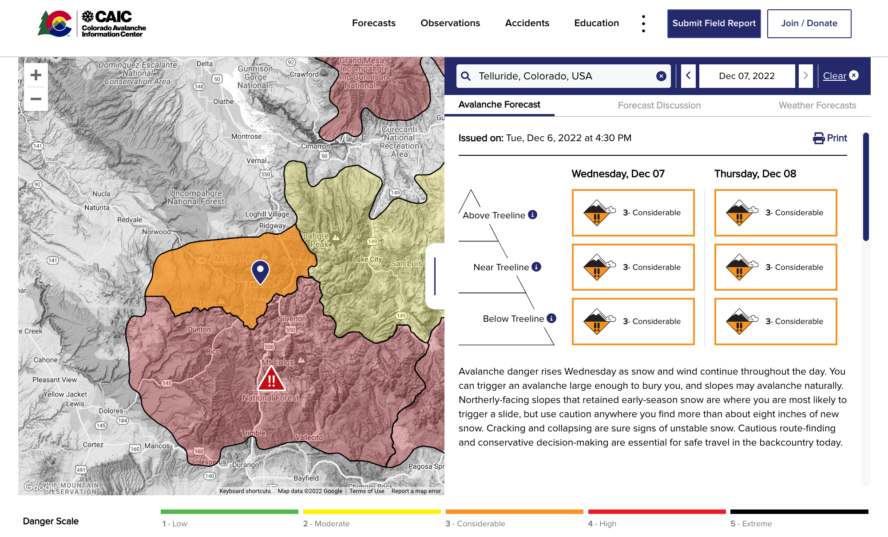

Typically, avalanches are the greatest single hazard to navigate in the backcountry. Checking the avalanche forecast and being aware of the potential for changing conditions is an integral facet of the planning process.

You’ll have to continue to evaluate your hypothesis in the field. Avalanches primarily occur in terrain 32 to 38 degrees in steepness, and you should know beforehand the steepness of the terrain you plan on skiing, including what is above you.

Rockfall and Crevasse Fall

In guiding, we often say we have the risks of falling off the mountain, into the mountain, or having the mountain fall on us. Depending on the terrain, we may need to mitigate all three of these risks at once. The simpler terrain you choose, the fewer hazards you’ll have to navigate.

For more information, Rob Coppolillo, an IFMGA Guide who splits his time between North America and Europe, shares additional backcountry skiing tips including advice on avalanche awareness and managing risk.

Preparedness

You should always strive to have comprehensive awareness of the terrain around you, a plan for ascent and descent, and for avoiding hazards like cliffs, terrain traps and other features that amplify the consequences of an avalanche or fall.

Have backup options if conditions are not what you expected, or if weather prevents you from reaching your goal. You should know the weather forecast for the day and into the evening, and an idea of this will affect your objective or the odds of rescue.

Along with all of this, you should carry an emergency kit including first aid, extra warmth, packable shelter, repair items, downloaded maps and extra charging capability for your devices, and a satellite communication device like a Garmin InReach. You’ll find a more comprehensive gear list below.

Humility

Falls in big terrain can quickly become serious. If you’re just getting started backcountry skiing know that it is not all about the steep lines you see in the movies. Working your way up to skiing challenging and complex terrain takes years.

Even if you’re a strong resort skier, don’t try to be a hero in the backcountry until you have a foundation of experience. We call this getting “over-terrained” and it can cause falls and other serious accidents. Start small and don’t rush the process.

Who Should Try Backcountry Skiing?

A desire to explore, willingness to learn and be flexible, and the grace to accept failure and challenges are all vital characteristics for new backcountry skiers. Moving uphill with a pack and skis on your feet over variable alpine terrain also invariably requires good cardio fitness.

How fit do you need to be for ski touring?

Simply put, if you’re in good physical condition, backcountry skiing will be much more enjoyable. If you’re not dying to keep up on the skintrack, you’ll have more mental bandwidth for situational awareness.

That bandwidth will allow you to focus on developing your mountain sense, route-finding abilities, and snowpack assessment. If you feel good hiking all day with a pack on mountainous trails, and can ski most black diamond runs on a ski resort with confidence, you’re in a place to try backcountry skiing.

Planning Your First Backcountry Trip

We’ve covered the who, what, and why, now let’s dive into the how of preparing for your first ski tour.

How to access the backcountry

You guessed it: How to plan your trip and access the backcountry differs in Europe and North America.

In Europe, resources for planning are often much more robust and comprehensive. Uphill access is essentially everywhere there is infrastructure, available on almost every ski resort. No one will tell you that you can’t exit the resort boundaries wherever you please.

“Off-piste areas exist within the boundaries of the ski resort, and these areas are only mitigated for avalanches if they are above on-piste, groomed terrain,” Larson adds.

In North America, uphill access within ski areas is generally limited; you must enter the backcountry from the resort boundary in specific places, often through backcountry gates. Much of North American ski touring takes place entirely outside of ski resorts, on public land.

North Americans tend to have more of a “secret stash” culture. This can constrain information in some capacity, but can also leave it as more of a process of discovery for those getting into the sport, which can help limit those without experience from getting into trouble in complex, committing terrain.

Considerations for rescue

Europe:

You often hear in the backcountry community about how expeditious rescue can be in the Alps. There are large, government-funded, paid and highly trained rescue teams on standby at all times to carry out rescues.

“Depending on the area, ski patrol may also step in to assist with rescue in Europe. Generally for patrol rescue, you’ll have to pay more than for a state-funded helicopter rescue. But in the Alps, you’ll always want to add the additional insurance on to your lift ticket, which for a day pass costs as little as two euros,” says Larson.

North America:

Rescue for most accidents on public lands falls onto the shoulders of local Search and Rescue (SAR) teams, which vary widely in terms of resources at hand, number of members, and ultimately, response time. Many SAR teams in the United States operate with a team of mostly volunteers.

Within the boundaries of National and Provincial Parks, professional mountain rescue teams are stationed in the field and ready to assist when they deem it appropriate to intervene. Climbing rangers in places like Mount Rainier and Grand Teton National Parks assist with many backcountry ski-oriented rescues each year.

Rescue generally hinges on the amount of use in a particular area.

Higher traffic also means a higher likelihood of rescue potential if things go awry for your group. That might mean for beginners, that ski touring in more trafficked areas—such as off-piste skiing in Chamonix—is usually sensible. As backcountry skiers end up further into the mountains, they also inevitably find themselves with a lower likelihood of reliable rescue.

Ideally, skiers should be self-sufficient no matter where they are recreating.

You should be prepared to both care for your partners in the case of emergency, and have the proper tools and knowledge to execute a self-rescue if necessary.

Many factors, like inclement weather, approaching darkness, or limited resources may prevent a timely rescue. Do the research on where you’re planning to ski, and decide if the remoteness of your objective is within your ability level to manage. If not, find somewhere more accessible for now and work up to those bigger, more distant goals.

Finding Ski Partners and Mentors

To be able to backcountry ski without the direction of a professional guide or an experienced group of peers that you trust, there is a long list of skills that you need to dive into and sharpen before expecting to have success in the backcountry. You’ll need to hone in your uphill technique, snowpack assessment, route finding, ability to seek out the best quality skiing, and more. Strive to limit group size and be discerning about getting out with partners that you know and trust.

It’s essential to find receptive, communicative partners with similar risk tolerance, an experienced mentor, or to seek out guided instruction. Skiing in the backcountry with a guide can help expedite your progression through the steep learning curve that the first couple of years inevitably bring. (Sometimes, even pro guides hire guides in the backcountry when exploring new terrain, in order to get familiar with the unfamiliar faster).

“In general,” Larson says, “North Americans are often more hesitant and usually better prepared by the time they get into the backcountry. Usually people have taken medical and avalanche courses before getting out and ask the same of their partners. Europeans are generally more inclined to hire guides to maximize their time.”

Find active skills that you can practice, like beacon searches, probing technique, setting a skintrack, or improving kickturns.

Avalanche Awareness and Online Bulletins

A key element of backcountry skiing is keeping a finger on the pulse of the seasonal story of the snowpack and the avalanche potential where you ski. If you take a trip to another mountain range, you’ll need to do your homework, because it’s likely you’ll find a distinctive snowpack story.

Embrace becoming a snow nerd

I won’t dive too deeply into the endless nuances of forecasting or how to assess terrain for avalanche risk. There simply isn’t enough space in a few paragraphs, let alone an entire article (or book, for that matter) to articulate all of the factors you need to be on the lookout for. You need to spend time in the snow.

Realistically, it takes professional instruction, constant reflection and many days spent out in the snow. As a budding backcountry skier, you should strive to fully embrace the practice of becoming a snow nerd. There is no substitute for getting out there.

Start with major red flags

Pay attention to any rapid changes: high amounts of snowfall, wind transporting snow, large temperature increases and rain on snow events should cause you to pause and reflect. The best evidence that avalanches may occur is observing recent avalanche activity—this is a flashing light that the snowpack is telling you to avoid certain slopes.

Avalanche forecasting resources

As with rescue, avalanche forecasting varies widely depending on location. Some more remote ranges have absolutely no online resources, whereas zones seeing a high concentration of use, like the Front Range of Colorado or the Chamonix valley, have government subsidized avalanche forecasting and public webpages.

The avalanche bulletin is quite different in the United States and Canada compared to Europe. “North America leans heavily on community submitted observations, while Europe only publishes observed data directly from forecasters,” says Larson.

Become familiar with the bulletin in your area and how to read it, most importantly to determine the current avalanche problem and danger rating.

Avalanche education

In the North American system, you’ll want to take a formal avalanche course—the sooner in your progression, the better. There are a variety of approved course providers in North America. I teach the Silverton Avalanche School (SAS) curriculum, and you’ll also see a lot of AIARE courses throughout the US.

In Europe, there is not a standardized national system of avalanche education, “so the learning process looks different,” says Larson, noting that “people are exposed to ski touring earlier.” Since it is more culturally pervasive, mentors and experienced partners are perhaps easier to find. If they are interested at a young age, many high schools and universities have ski clubs that offer avalanche education as a component.

“There are countless alpine clubs for adults, too,” Larson adds, noting that many of those looking to ski off-piste find their introduction to avalanche awareness and glacier travel in a club setting.

Navigation resources

Laying the framework and proper planning for backcountry ski touring could take up another full book (as could many of these topics). Look at maps, and have the map for the area that you would like to explore available in digital form, and consider a physical copy for more committing days or overnights.

Apps like Gaia and CalTopo work around the world, and will show you your position on a map in real time, so long as you have the map downloaded to your phone. In Europe, additional mapping resources like FATMAP have incredibly detailed information and show routes overlaid on satellite imagery, useful for setting goals and planning for future objectives.

There is always more to learn

Some of the best advice for new backcountry skiers is to never feel like you’re an expert. Keep seeking out instruction, building new skills and uncovering techniques to gain efficiency.

For traveling off-piste and eventually outside of the ski area in Europe, knowledge of glacier travel is essential. Seek instruction from a qualified guide or instructor in your area to learn crevasse rescue if you’re planning on skiing in glaciated terrain.

Both Europe and North America offer a variety of levels of medical courses specific to outdoor recreation. At baseline, you should consider taking a wilderness first aid course for a better understanding of critical life threats and injury problem solving.

What Gear Do You Need?

The gear list for ski touring is inescapably long, which can be unnerving and financially committing. While backcountry skiing shares some common equipment with resort skiing, I find that I use almost an entirely different quiver. This list grows depending on the objective, as well, and if I plan to travel on glaciers, rappel into my chosen ski line, or camp overnight.

“Backcountry skiing, in a sense, can be kind of like golf,” adds Larson. “You wouldn’t do all of your golfing with one club.”

“I usually have a quiver of up to five different pairs of skis, all for different purposes and snow conditions. This can be daunting for beginners, and I’m not saying you need skis for all types of conditions. But it’s better to buy a pair of skis and bindings that are purpose built for going uphill, rather than a heavy, complicated cross-over binding ‘that does neither thing very well.”

Technical Gear

-

- Backpack: Around 30L of capacity is ideal; consider the potential merits of an avalanche airbag pack if you primarily ski in alpine areas.

- Avalanche Transceiver: Also called a beacon. Look for a modern, three-antenna beacon with a flagging function. Most guides and patrollers prefer the Mammut Barryvox.

- Shovel: Made of metal, lightweight, able to be disassembled and packable.

- Probe: At least 240 centimeters long. Practice quick assembly, and don’t store it in your pack in the sleeve as this creates an extra step before rescue.

- Backcountry Touring Skis (or splitboard): We could dedicate an entire article on how to choose backcountry or alpine touring skis, but think about what kind of ski touring you want to do and choose accordingly. For a quiver of one, I look for something in the 95-105 cm-width underfoot range, with flat tails to accommodate skins better and not too much rocker in the front for easier climbing on the skintrack. Splitboarders may want to consider a directional twin board for more versatility. Look for something on the lighter end of the spectrum without metal in the core construction.

- Skins: Some models have more glide, others have more grip: prioritize one or the other depending on the nature of the tours in your area. Extra grip can help beginners from slipping backwards on the skintrack early on in the learning process.

- Boots: If you’re just getting started consider looking for a boot that can work both with a pin binding and an alpine binding.

- Bindings: I love the tried and true Dynafit binding, and have found that they achieve the best balance between uphill and downhill performance.

- Poles: Ideally poles with a collapsible mechanism, for changing terrain.

- Garmin InReach: In my opinion this is an indispensable piece of kit no matter where in the world you are skiing. It can assist with communication, navigation and facilitating a rescue if needed.

- Repair Kit: Should include items like ski straps, a scraper, wax, a small knife, multi-tool, and extra pieces specific to your equipment.

- First Aid kit: An introductory course will teach you what you should carry, but think about what injuries might occur out there and build a packable kit accordingly. Don’t go overboard and make it too bulky—strike a balance between preparedness and weight.

- Snow study kit: This can be a more advanced item, but when you progress to digging pits to assess the snowpack, you’ll need items like a snow saw and cord to conduct stability tests.

- Rescue sled: I always carry a lightweight rescue sled that doubles as a shelter in case of emergency.

Outerwear, clothing, and layering

-

- Brimmed hat: A packable five-panel hat offers protection from the sun on the uphill.

- Warm hat: For extra warmth.

- Buff: The buff allows me to use less sunscreen and protect my skin from wind.

- Insulated Jacket: Whether the weather is cold or not, I consider a puffy jacket as part of my non-negotiable emergency kit.

- Softshell jacket: In sunnier climates where I don’t need to protect from precipitation, I prefer a soft-shell jacket for backcountry skiing since it’s lighter and more packable.

- Gore-Tex jacket: If you’re expecting to deal with heavy and wet precipitation or very strong winds, a gore-tex shell can provide superior protection from the elements.

- Softshell Pants: I typically prefer soft-shell pants for backcountry skiing if conditions allow, since they’re more breathable and less restrictive to movement.

- Vest: This is an optional additional insulating layer, but I like the vest as an option to add a bit of warmth without as much bulk.

- Sunglasses: I like a pair with lenses rated for glacier travel. Photo-chromatic options can also be helpful for days with changing light to maximize visibility and protect your eyes.

- Goggles: A wide, interchangeable lens is best for variable conditions. Don’t wear your goggles for uphill travel. They’ll fog up quickly and it will potentially impede your visibility for the rest of the day.

- Helmet: Opinions vary widely on this one, but I always ski with a helmet in the backcountry, and I feel that they prevent a lot of traumatic injuries.

- Long underwear: Wool is my choice since it maintains warming properties even when wet

- Ski socks: For touring, I look for something wool and with minimal cushion to prevent bunching and blisters.

- Gloves: I wear lighter liner gloves for protecting my hands on the uphill and then switch to insulated leather gloves for downhill.

- Water and snacks: Don’t forget to fuel and hydrate while you’re out.

If you’re not ready to commit to buying all of the gear, look for AT-capable boots that fit well; from there, you can either rent the rest of the gear, or go out with a guide service that can provide equipment for you and teach you how to use it properly.

Best time to go ski touring

For me, ski touring season typically starts in November and ends in July. However, peak season is typically March to early May in most parts of the world (depending on the hemisphere).

Without going into it too deeply, a continental snowpack becomes significantly less avalanche-prone in the spring, once melt causes problematic layers to transform and cohere with the rest of the snowpack. During the thaw, it often becomes more a question of timing, rather than avoiding a specific avalanche problem. A formalized avalanche course or informational outing with a guide can familiarize you with the types of avalanche problems and when to consider them.

Additional Key Skills for Ski Touring

The foundation for ski touring is downhill ski technique. One of the easiest ways to improve your backcountry skiing: Spend more time skiing.

But, there’s a long list of other nuances to dial in to feel confident on the skintrack.

Transitions

Improving your transitions takes practice. Quick, efficient transitions are a mark of a ski touring veteran. The gold standard would be aiming to be ready to go from uphill mode to downhill mode in less than five minutes. Bonus points if you can rip your skins off of your skis while you still have them on; this not only makes you look pro, but it also prevents snow from getting into the interface between boot and binding, which can cause your skis to unintentionally release.

Skinning technique and tips

If done properly, skinning uphill should feel as effortless as possible. You want to use your skis to glide forward, initiating movement from your hip flexors and keeping the skis on the snow. Many beginners make the mistake of picking up the entire ski, as if they were walking with snowshoes, which is extremely fatiguing. Take advantage of the forward glide. When setting a track, learn the art of reading terrain to create the most energy efficient path forward while always considering overhead hazards and avalanche risk. Keep the angle of uphill consistent and moderate to minimize slipping backwards.

Resources to Continue Learning

One of the biggest benefits of our digital age is the proliferation of resources available to help you learn a new skill. There are countless online forums dedicated to backcountry skiing and many books that can help you learn—far too many to list here. At minimum consider procuring a copy of Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain by Bruce Tremper for more information on assessing avalanche risk.

Value in hiring a guide

Going out on a backcountry ski tour with a guide can help facilitate your progression into the sport in a risk-managed environment. There are many elements of backcountry skiing that I haven’t even touched on here, which are best learned in the field. A guide can help walk you through backcountry considerations in real time, and provide tips and tricks to fast track your success.

Some of the Top Ski Touring Destinations in the World

Part of the appeal of ski touring is discovery. You can have the time of your life backcountry skiing around the world: from Japan to New Zealand, Alaska to France, Vermont to New Mexico, Argentina to Kamchatka… you get the idea.

Here are some of the most well-known and deservedly popular destinations:

Chamonix

-

- The indisputable epicenter of ski touring is the Alps, primarily spanning France, Switzerland, Italy and Austria. At the heart of this is the Chamonix valley, one of the best places for backcountry skiing in Europe. The home of the popular Haute Route and the Vallée Blanche, Chamonix offers incredible ski touring for all levels. With five resorts in the valley alone, and the precipitous Aiguille de Midi whisking skiers quickly 8,000’ up from town, there are many lifetimes of amazing skiing with unparalleled access. You can read all about ski touring in Chamonix here.

Canada

-

- Canada has some of the best backcountry skiing in the world, and the Coast Range boasts some of the best snow conditions you’ll find anywhere. Here you’ll find amenities with great access to remote, stunning locations. Perhaps the best bang for your buck in the great white north is to seek out lodge-based helicopter skiing, and Rogers Pass is on almost every backcountry skier’s shortlist.

- In recent years, the backcountry has seen a major surge amongst skiers looking for pristine powder beyond the resorts, and Canada is well-suited to accommodate them. The backcountry ski lodges in British Columbia offer unprecedented access, and comfort, typically without crowds. Thanks to a balance of legendary snowfall, bluebird weather, and dry pow that stays fresh for weeks, ski touring from the huts of British Columbia can almost assure an uncompromised trip.

USA

Alaska Range

-

- While primarily known for big mountain helicopter skiing (at places like Valdez), Alaska—the last frontier—is home to some unbelievable ski touring. Mountain Trip hosts several plane-accessed backcountry base camp trips, with access to inspiring, glaciated steep terrain. For those looking to take their steep skiing to the next level, this is the place.

Jackson Hole

-

- There’s a reason many of the best backcountry skiers make their way to Jackson Hole, with the greater Teton area one of the great ski touring destinations in the country. Ski touring at the Jackson Hole Resort provides a gateway to incredible sidecountry terrain, while the options in Grand Teton National Park are endless, spanning the gamut from mellow meadow skipping to incredibly technical descents.

Telluride

-

- Both Larson and I have chosen to call Telluride, Colorado in the San Juan Mountains home. Backcountry skiing in Telluride seems to be the perfect blend of the American West and the Alps, with jaw-dropping alpine views that rival anywhere, some of the best access in North America to backcountry and resort-accessed sidecountry skiing, hut-to-hut traverses, and inspiring peaks. The San Juans provide unquestionably one of the best environments for learning about avalanches, with one of the most consistently dangerous snowpack structures in the country.

Cascades and the North American Rockies

-

- The prominent volcanic peaks of the Cascades and the long spine of the North American Rockies are home to countless outstanding ski touring destinations as well, each with unique subcultures and communities.

Japan

-

- For an exceptional cultural experience and the deepest powder on earth, head to the Land of the Rising Sun. One of the best ski touring spots in Japan is in the northern part of the island, Hokkaido, which almost guarantees face shots thanks to annual snow totals approaching 1,000 inches (yes, you read that right). Volcanoes like Mount Yotei offer otherworldly backcountry descents and most resorts are similar to the Alps with great off-piste skiing. Ski touring in Japan is hard to beat.

Norway

-

- Ski touring in Svalbard or from the remote Lyngen Alps are some of the most unique places in the world to ski, offering true, remote adventure. Sail-to-ski expeditions offer the mind-bending experience of skiing incredible terrain with a view of the ocean below. You’ll have to be on the lookout for polar bears and stave off seasickness to seek out the goods.

Iceland

-

- Iceland is an up-and-coming destination. Nowhere else can you travel through lava fields and icy fjords, glaciers and volcanoes, and then ride down all the way to the ocean all on one trip. Skiing on the Troll Peninsula, a high lava plateau that bears the brunt of northeastern storms, has great corn snow and fine weather well into June, while sailing and ski touring in the Westfjords takes you to some of the furthermost reaches of the Earth, For more information on ski touring in Iceland, you’ll want to go right to the source: Jökull Bergmann is the country’s first IFMGA Mountain Guide and a local legend.

Antarctica

-

- Speaking of the edge of the world, ski touring in Antarctica is a place few others have ventured. You’ll encounter blue seracs and towering sea-ice, cold, chalky, and above all, dependable snow, and plenty of wildlife, such as gentoo penguins, black-browed albatross, snow petrels, leopard seals and whales.

As a disclaimer: By fabricating a list of “hot spots,” I’m inevitably leaving out so many amazing places that hold great backcountry adventures. It’s on you, as a new backcountry skier, to constantly seek out that sense of discovery. Find the place closest to you where you can get into the mountains consistently to build your basis of skills, and that will be your “hot spot” to level your focus. From there, the exploration is endless.

Seek Out Your Next Steps

By now, hopefully we’ve answered the question: what is ski touring? My goal is that this serves as an introduction to give you the tools to start building your backcountry foundation. Remember that true mastery takes decades—no single article, outing or course will ever make you an expert—and there is always more to learn.

But keep in mind what you’re working towards: few things in life rival the accomplishment and wonder of topping out on a high, isolated peak with your skis, then arcing turns back down in an inspiring setting.

I know that I’ll keep chasing these moments as long as I can. I hope you do, too. The adventure is yours to discover.