When I first arrived at Indian Creek 14 years ago my only concern was if I was worthy to onsight the 5.10 test pieces.

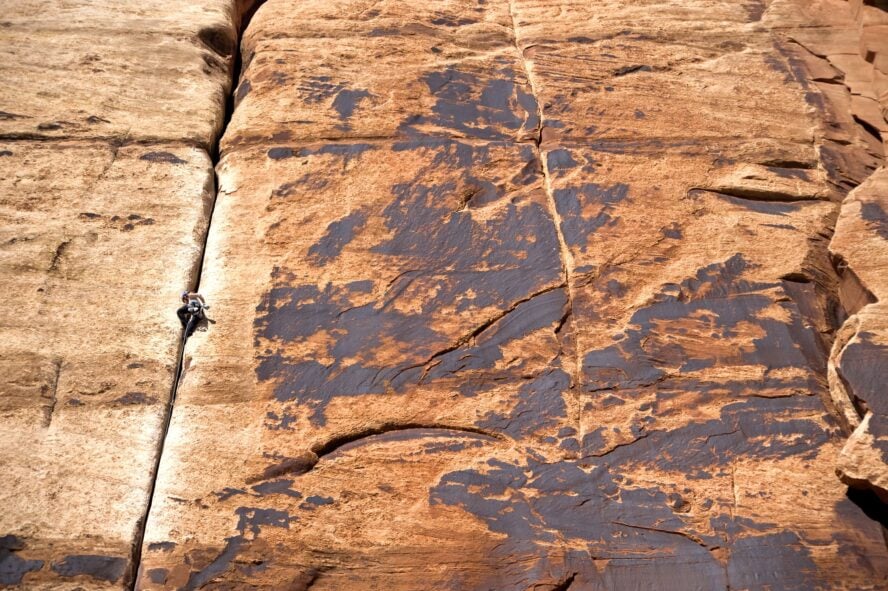

I had waited a decade and a half to come climb some of the best cracks in the country and was going to make the most of my trip. Driving in I was in awe: the epic orange-red stone raged against the cobalt blue skies, the soaring splitter cracks intimidated in their verticality.

Then I found my line.

I Didn’t Listen… But I Learned To

The crack was unrelenting. My arms were lead.

I was leading 30 feet above my last cam and only had museum-quality gear left for protection. It was 50 feet more to the top of Amaretto Corner with one archaic rigid stemmed cam at my disposal. As I punched my way up, I was buoyed by hubris, clunky pro, and insecure hands and feet.

Before I arrived, I’d heard a lot about The Creek:

The pitches are so long and so splitter you might need 8 to 10 of the same size cams; expect to climb a couple grades below your level; don’t go there until you are ready.

I hadn’t listened but managed the send without calamity nonetheless.

Still, I had a sense the rock gods were laughing at me.

I had parachuted in from far away—as 95% of climbers here do—and only really cared about my experience climbing. I’d leave without thinking much more about the area, or the larger impacts of recreating here, until years later.

In the end, everything they said about The Creek was true, but what I hadn’t yet heard was far more important.

14 Years Since My First Visit and a Lot Has Gone Down

That first trip, I was relatively clueless about Indian Creek. Yes, I admit ignorance despite having a degree in Native American Studies and having worked with tribes and land managers on the West Coast about how to recreate sensitively on Native and Federal lands. I often think now, how might my actions have negatively impacted the area?

The impact of recreation

Frankly, there is so much more to Indian Creek than having enough cams and the technique to send. The region is in flux and under threat from overuse and a lack of oversight.

To be on the ground today is like a new chapter from the Old West. Instead of law-evading gunslingers it’s cam-slingers. It’s not by the dozens like the days of yore, it’s by the thousands. It’s not just climbers, it’s all flavors of recreaters: hikers, 4-wheelers, mountain bikers, and on and on. Since COVID, user numbers are through the roof and management is, well, a clustermuck.

As a result, the area is being jeopardized.

What’s at stake is access—potentially restrictive red tape and regulations. Or worse. We could lose the area to resource extraction. Both are realities if climbers don’t do the right things.

I wanted to know, as a climber, how can I go without aggravating existing issues? We can no longer be ignorant if we want to climb at Indian Creek, now, or ever again. Below are some of the big risks, and further on we dive into some potential solutions.

Major Challenges Facing the National Monument Today

1) Uncertain boundaries and oversight

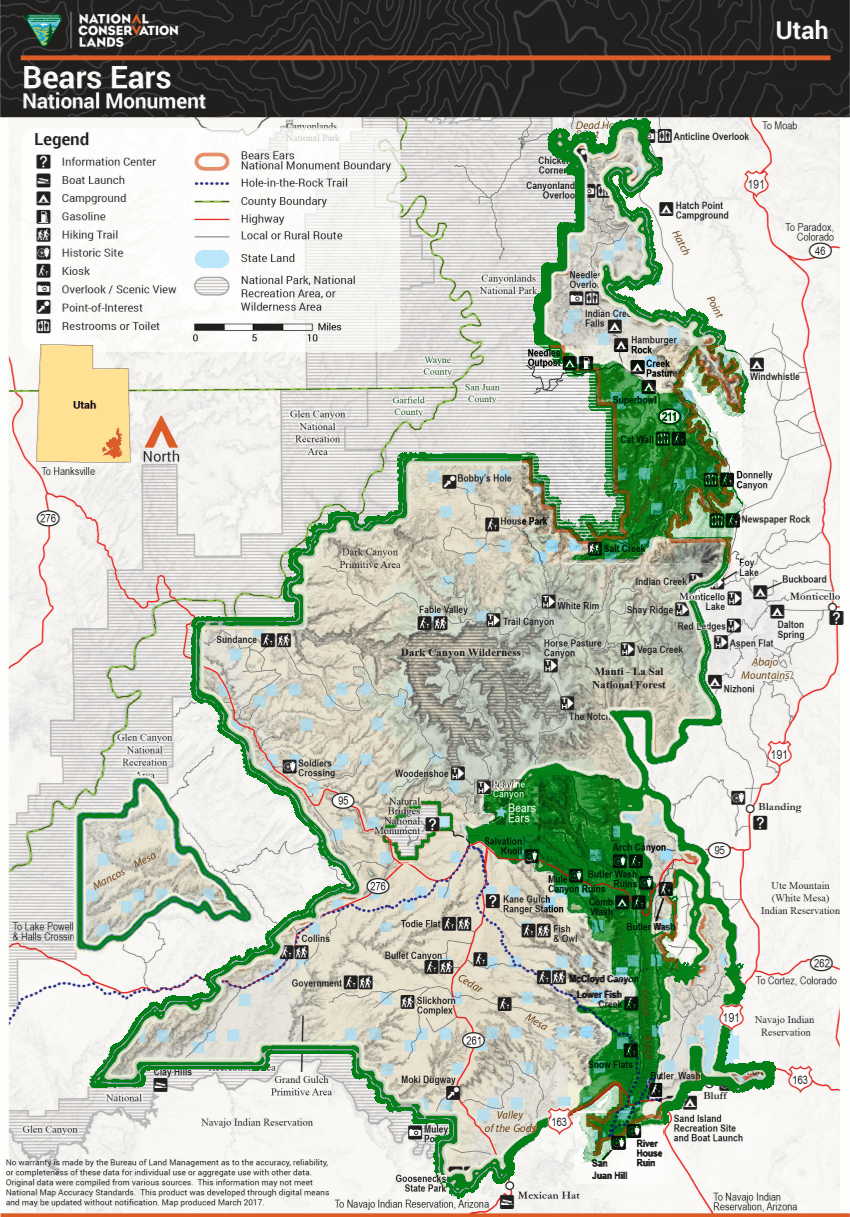

Federal Land jurisdiction and boundaries for Bears Ears National Monument are up in the air. The Trump administration reduced the National Monument to 15% of the size established in 2016, leaving a northern Indian Creek Unit and a southern Shash Jaa Unit.

Lawsuits from the Access Fund, Patagonia, and others—to restore the Monument—are now on hold as the Biden administration reviews the boundaries. It is not yet known where they will officially land.

Today, Federal land management organizations are often resource-challenged and in need of retooling to incorporate differing user groups. In light of increased recreational usage, these issues are magnified for the two primary land supervisors.

Bears Ears is jointly overseen by the Forest Service (FS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and the organizations have differing opinions of the current boundaries. The BLM website reflects the downsizing by Trump while the FS site does not. There are also five tribes—the Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute, and Uintah Ouray Ute—that lay historical claim to the area and hope to have more of a say in management.

In the end, it’s unclear who exactly has jurisdiction or what the rules are, and as a result they are not always enforced.

2) Damaging the rock we love

The desert rock is sensitive. Just look at the wearing away of patina on the stone flanks of popular crack climbs like the Incredible Hand Crack or Generic Crack. Climbers have a real physical and visible impact on the rock, where they camp, make trails and relieve themselves.

With a huge uptick in usage the evidence is becoming clearer that there needs to be more regulation by the land managers, and self-regulation by climbers, to best deal with the impacts.

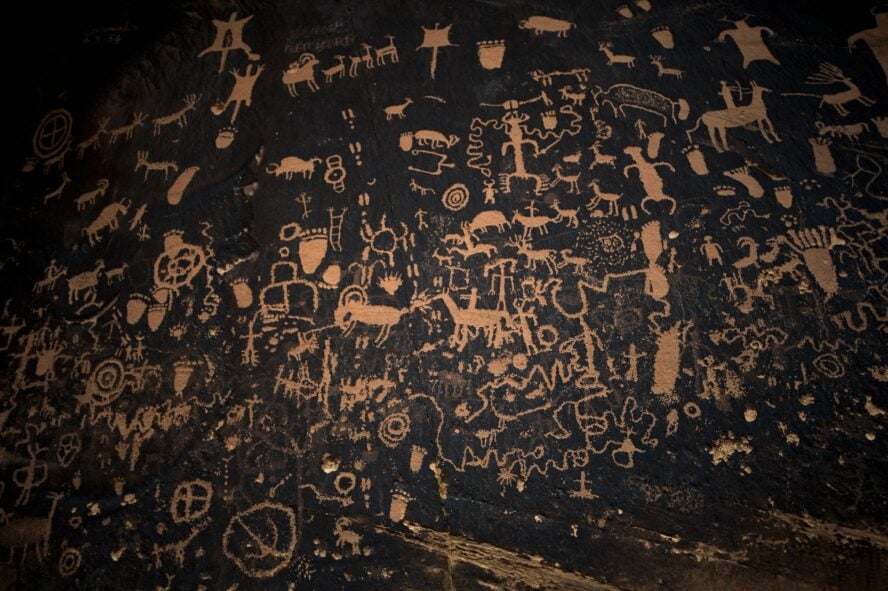

3) Cultural insensitivity and outright racism

Locally there has been ignorance in the ethics of climbing development. For example, a few months ago a climber bolted over 1,000 year old petroglyph panels from the Fremont culture near Arches National Park. (See the Access Fund’s Climbing on Sacred Land webinar for greater context and discussion between climbers and Natives on this). A few weeks after the bolting, white power symbols were carved on “Birthing Rock”, an historic petroglyph site in Moab, another top climbing area close by.

Actions like this, whether from climbers or otherwise, jeopardizes access for all.

4) Multiple historical stakeholders

As climbers we don’t operate in isolation from the other groups that use the area. Natives in and around Bears Ears National Monument are still actively engaged in the region as are operating historic ranches. We have to be aware and sensitive to their needs and uses. Often we are so hyper-focused on our own experiences we don’t realize, or downplay, our own impacts.

What We Can Do as Climbers

It is every climber’s responsibility to be part of a solution and not jeopardize things by inaction—or worse—by misinformed disregard. Here is a short list of what we can do in Bears Ears National Monument, and pretty much anywhere we climb, to keep this resource available for everyone moving forward:

-

- Respect the land and cultural resources: know where you are because if you don’t you are likely to trespass or damage sensitive areas. To really develop respect means to listen to the land and pay attention to all that is going on there

- Recreate sustainably: engage and explore in a way so that future generations will be able to enjoy it too

- Stewardship: pack in, pack out; get versed on bolting ethics; be aware of and respect petroglyphs and pictographs by learning how to identify them (and then don’t climb on them)

- Get involved: with management plans, stakeholder engagement, and local climbing organizations. Speak up and help inform others when you see their actions jeopardizing an area

- Reduce impact by… not climbing: sometimes it’s best to enjoy the landscape in the horizontal plane. Get a flower guide or bird book and learn about other tenants here. There are Moki steps for those that look; the Ancestral Puebloans and other Natives here were bad ass climbers too

Action on the Ground

To learn more about what is happening today, I called up some people I admire for their work and knowledge of Bears Ears National Monument. Their responses provide additional context, especially as it pertains to the future of the area. These interviews have been edited for concision and clarity.

The first person I contacted was Jason Keith. I first spent time with Jason in 2005 while living in Northern California where I had started an LCO (local climbing organization). Jason, the lead liaison on public lands issues for the Access Fund, flew out to assist us in dialoguing with Redwood National Park and local Native tribes. This kind of negotiation and appreciation for Native voices was still developing at the time.

As evidenced in the Climbing on Sacred Land webinar, there are still some strong opinions regarding climber usage from a Native perspective and the Access Fund did not have a long history of supporting tribal interests; their focus was rooted in climber advocacy. Since then, things have been changing.

1) Stewardship starts with us climbers

Jason Keith – Senior policy advisor for the Access Fund and the American Mountain Guides Association

“With Friends of Indian Creek, we are supporting a multi-year project led by the Access Fund to help with several issues. It starts with putting two climbing stewards on the ground during peak season, which should launch this fall. The aim here is to help with climber outreach, education regarding resource sensitivities, and generally helping to manage conservation efforts.

This Access Fund program can help fill the management and budget gaps that the BLM faces [and be present to reach climbers directly].

One big project that Access Fund will be pursuing in the short term is producing a manual (much like our raptor manual: Climbing And Raptors: A Handbook for Adaptive Raptor Management) that outlines best practices for protecting and respecting cultural resources at climbing area. Our plan is for Natives voices to write and review this document.

Earlier this year, we performed a survey with Dr. David P. Carter of the University of Utah, in order to document practices, perceptions, and management preferences of Indian Creek climbers. The survey showed that most climbers were in favor of working with Native American peoples and supported the restoration of Bears Ears National Monument.”

2) We need to learn the stories (historical and current) of the places we climb

Renan Ozturk – Award-winning filmmaker and mountaineer living in the Southwest

“Climber’s think they are informed but often they aren’t, especially when it comes to Native perspectives.

I was pretty clueless until I did some Native perspective films and got involved. I’d say 50% of climbers have no clue about the history of Natives or Native perspectives so you have to speak to climbers without alienating them. We can’t villainize climbers, that’s not the point [we need to educate and work together towards protecting the lands we care about].

However, hardly anyone is telling the native stories. Storytelling is tricky with all the brands wanting to capitalize on the beautiful location and get their pretty photos with the gear and the climbers, but the outdoor industry in general is not stepping up and sharing the native story; it’s just about fun in the sun climbing.

“Every place in the desert is fragile.”

I’ve found it to be super hard for the outdoor industry to support a longer-form film about the issues that could make a real difference. We would like to do one about Bears Ears National Monument, but I know funding will be a challenge.

With that said, Bears Ears has been popularized in the media because of the Monument status and the subsequent reduction by the Trump administration. Now, we are seeing a huge increase in recreational usage. But when you go on the website for Canyonlands or look at social media about these places, there is nothing about the native story or the impacts from so much elevated use.

There needs to be custom management plans and more regulations. However, climbers, especially the more avid ones who have been going to these places for decades, don’t like this.

We likely won’t lose our ability to climb here, but Indian Creek might go to a permit process eventually. Even the Access Fund acknowledged this at a recent meeting [along with other stakeholders] at the Canyonlands Research center with the local ranchers and the Friends of Indian Creek.”

3) Respect the land and cultural resources

Chris Schulte – Friends of Indian Creek board member, writer, pro climber with Adidas/Five Ten

“I have been climbing at Indian Creek for 25 years and it’s my favorite place in the desert. As a professional climber I have a responsibility that if I bring newer climbers in, I should help them understand the value of this place.

You must be aware of the Indigenous presence. It’s a cemetery, a church and a home and has been for several thousand years. The scratchings on the rocks might be 1,000 years old but the Natives are still here and recharge here.

Walk carefully and look down and look up. You are walking through time. Tread carefully. I feel like we all ought to educate ourselves to a degree where we can move in sensitive areas with discretion and respect.

“It is not an amusement park.”

All populations and all interest groups have to get along, but we really must remember who was here first. This is not just about having fun.”

4) The key will be management plans and stakeholder engagement

Aaron Mike – Diné (Navajo) mountain athlete, rock climbing guide, and Access Fund Native Lands Coordinator

“My position at the Access Fund revolves around advocacy and education at the intersection of Indigenous sovereignty and Public Lands management, which typically includes working with organizations that represent Tribal interest, as well as organizations like the US Forest Service and Outdoor Alliance.

There are many tribes and their respective goals are unique. It is important to follow their lead on their lands. One of the biggest challenges, even as an Indigenous man, is in developing tenets of how to approach individual tribes respectfully in order to illuminate tribal goals and codify oversight into management plans.

I believe that my work helps respective local communities to manage their land resources in a more sustainable and effective manner. Although I do not work for or speak on behalf of any specific tribe, I am hopeful that the combination of my heritage, technical experience, and position will aid tribes in having more of a presence in public lands management and bring new opportunities to their local communities.

“I want future generations to be able to feel inspiration from these wild places just as I am now.”

Regarding climbing, there hasn’t been as much pushback from the tribes as you might think, despite the bumpy relationship caused by historical rock climbing events that have occurred on Navajo Nation.

This was most pronounced in 2019 when a colleague and I presented to tribes present at the Navajo Nation Sustainability Conference in Flagstaff, Arizona. Rock climbing has had a long-standing taboo feeling on Navajo Nation and as I was able to communicate modern climbing techniques that reduce impact on the rock, available sustainable management tools, and potential favorable economic benefits, interest seemed to build with the lens of benefiting tribal and outside communities. Many local and nation-level Navajo officials were very excited to hear about potential opportunities in the rock climbing industry and outdoor recreation in general.

I am a Navajo man who grew up on and off of the Rez. Growing up, my family greatly valued Navajo tradition and living with a deep connection to land through things like ceremony, sheepherding, and piñon hunting so this has informed my deep relationship with wild spaces. The land is a living being and our oldest ancestor, therefore sacred, so it’s important to constantly give back when we take experiences.

I think that most people want to appreciate and aid wild spaces, but maybe don’t realize that they can do this by gaining a deeper understanding and comprehension of the history of the land. From here, we can draw important lessons. We need to realize the lineage of our cultures and accept our place in the continuum, while also understanding that the living land was here long before us. When we are on land, we need to step back and feel the gravity of where we are. For me, this also helps to thoroughly enjoy the entire experience of the places that I visit.

In terms of access to education on respectful recreation on sacred land, do not be afraid to reach out to tribes directly. We are all learners, and the best resource is from a direct source. Another prominent resource within climbing communities are LCOs. They have a ton of educational resources for safe practices, sustainable practices, and information about the land on which you are climbing on.”

I Think I’m Finally Listening

Last year I travelled back to the Bears Ears region with my partner, Rita. I was excited to share some of the classics I had discovered more than a decade before, but with new perspective.

The mesas were crowded with climbers despite the rising temps, and we roped up in the dazzling summer morning as a patch of darkened sky was pushing our way. There were gentle monsoon rumbles in the distance, in contrast to the blue sky. Rita demurred to the crowds and the coming storm.

As we walked onwards, Rita asked, “whose land are we on?” I was pretty sure it was BLM, but I thought again.

“Ummm, Utah Diné (Navajo)?”

Rita has Native blood from the Southwest. In her teasing but loving way she reminds me almost every day just how “white” I am. Thus I am learning to understand what this “privilege” really means.

She is also a solid climber with a profound respect for place. I listened when she suggested that we drive on and not climb that morning. Instead, we continued toward Mexican Hat, a forgotten aid classic up a mushroom capped spire at the edge of the southern Shash Jaa Unit of Bears Ears,

Despite my prodding, Rita opted out of standing atop the Hat, which today was more lightning rod than anything else. From the route’s base we enjoyed the microburst lightning storm with black clouds and virga—spectacularly regional shafts of precipitation that don’t hit the ground—over the picturesque Monument Valley just south of us. A rainbow shimmered in the August heat.

At that moment, borders, land ownership, stewardship all frothed forward in my mind. And I paused. I knew then where I was, feeling the gravity of the place. There was no need to climb.

Want to Learn More? Additional Resources and Organizations Involved with Bears Ears National Monument and Indian Creek

Utah Diné Bikéyah: The Diné (Navajo) in Utah provides critical tools, training, and technical support to the five Tribes—Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute, & Uintah Ouray Ute—who are leading the call to protect the Bears Ears cultural landscape as a national monument.

Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition: With representatives from the five tribes, the mission statement says it all: “To assure that the Bears Ears area will be managed forever with the greatest environmental sensitivity… where we can be among our ancestors… where we can connect with the land and be healed.”

Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Bears Ears: Both the BLM and the Forest Service share management roles here. There is an ongoing effort to include the five tribes who are important stakeholders and are actively engaged in the area, and who live nearby or within the territory. The site shows the currently reduced size of the National Monument. Permits are required for specific areas and it’s a good bet that permitting will expand to other sections in order to manage visitor usage and impacts.

Forest Service Bears Ears: The official site still shows the original boundaries, at well over 1,000,000 acres. This exemplifies the conundrum here: a lack of funding and clarity regarding what is included in the boundaries and who will be managing it.

Canyonlands Research Center: The center offers visitors a glimpse into the ongoing efforts by the Nature Conservancy to help increase knowledge and provide stewardship for the region.

Access Fund: The quintessential U.S. organization working on behalf of climbers to educate, help purchase properties to maintain access, and advocating for climbers as stewards.

Access Fund Indian Creek Climbers Survey: The Access Fund surveyed climbers to understand their viewpoints and awareness of issues at Indian Creek.

Indian Land Tenure Foundation: Know where you are climbing. This website shows where Native American tribes have lived historically and often presently throughout North America.

The Dugout Ranch: A still working historic ranch within Bears Ears National Monument advocating for regulation to mitigate impacts.

Access Fund Climbing Stewards: Learn about how the Access Fund is helping to mitigate management challenges by putting climbing stewards on the ground at Indian Creek.

Access Fund’s Climbing on Sacred Land Webinar: A great dialogue between Natives and climbers and the intersection both historically and currently.

Washington Post What Remains of Bears Ears: An in-depth feature regarding boundaries, history, and powerful drone footage of the cultural and archeological resources in Bears Ears National Monument.

Outdoor Alliance: The OA works to protect the places we ski, hike, climb, paddle, and bike. They bring together the voices of America’s outdoor recreation community to protect the outdoor experience for everyone to enjoy.

Want to climb at Indian Creek, responsibly? Join certified guides who know the proper local etiquette and enjoy a day out on some of the best crack climbing in the country.