The Best Places to See Wildlife in Yellowstone

Hiking through Yellowstone is like taking a step back in time. Experience some of the best wildlife watching in the U.S. in a land the human hand hasn’t touched for 150 years.

In the purple hues of pre-dawn, the lodgepole pines rise like great shadowy plumes alongside the trail as we descend into Hayden Valley.

If we’re lucky, we’ll catch a glimpse of what we’ve set out for: a grizzly, romping around the meadows before the heat of the day kicks in. If we’re extra lucky, there might be a cub or two tagging along. And even if we’re unlucky, we still get this sweet little walk in the woods, the soft thudding of our boots hitting the trail accompanied by the melodies of songbirds.

Soon, when the sun has risen and bears have returned to the forested shadows, we’ll continue into the valley, seeking out bison, beavers, and eagles from pullouts and overlooks. We’ve got a full day in the country’s last frontier for wildlife watchers, where these animals hunt, burrow, fly, breed, and live protected and unbothered.

To be clear, I don’t always rise before dawn—but in most places you can’t see grizzlies or wolves in their natural environment. I like having the option.

Pros and Cons of Wildlife Watching in Yellowstone

Yellowstone: A Last Frontier for Wildlife-Watchers (Like Myself)

I may be going out on a limb here, but I’m going to assume you’ve at least heard of Yellowstone National Park, as one of the best places to hike in the U.S., or otherwise. (Though, no shame if you haven’t! It’s a big world out there.)

To place it on a map, the park is nestled in the northwest corner of Wyoming, its borders bleeding into neighboring Idaho and Montana. The latter is where you’ll find me, in Gardiner, Montana, a little western village that sits right on the park’s northern border.

A piece of living history

Yellowstone is about as wild as you can get in the contiguous U.S. It’s been formally protected from development for a century and a half, and to this day, the park shelters all the native species that existed prior to 1800—though there have been some close calls.

By the early twentieth century, wolves, bison, and trumpeter swans were on the brink of extinction until careful protection and rehabilitation policies were established. Now the ecosystem is home to 300 different species of birds, 67 mammals, 16 fish, 11 reptiles and amphibians, and 1,160 plants (3 of which are endemic, meaning they’re only found in this area).

Other rarities include the lynx, bobcat and ever-elusive wolverine. There’s much much more too, including animals you are more familiar with—black and grizzly bears, moose, eagles—and others you maybe haven’t heard of before, like pikas and pronghorns.

My career getting (respectfully) up close and personal with critters

Before settling in the Big Sky State, I was a globetrotter. As a conservation ecologist and wildlife biologist, I’ve made my way around the world and to every continent—twice—having worked in Australia, Papua New Guinea, and Antarctica. I was in constant motion, navigating everything from expansive deserts to creaking icebergs, always learning about creatures big and small.

Eight years ago, with those experiences under my belt, I wholeheartedly committed myself to Yellowstone. It’s a place that’s just wild enough to offer the exploration and learning I love, but where I can still connect with like-minded wildlife lovers.

Today, I own In Our Nature Guiding Services, and we’ve got a great team of hearty nature-nerds, including Claire, a biologist and our in-house wolf expert; Susie, who plans trips and leads llama guiding tours; Cody, a fly-fishing virtuoso who also leads skiing and snowshoeing tours; Angela, who leads night-sky tours; and Nancy, who—and I would bet money on this—knows more about Yellowstone’s geothermal features than anyone else in the park. Perhaps the best part of this gig: I get to share my love for the natural world with folks from all walks of life.

So that’s how I ended up here, following a herd path across the Hayden Valley floor, keeping an eye out for scat and paw prints. As the early morning sun comes over the horizon, we follow a stream, which cuts through the plains and reaches out toward sloping mountains. Their peaks just catch the light, granting a painterly quality to the landscape.

Creating a work of art: The world’s first national park

Yellowstone has long captured the imaginations and romanticisms of those seeking nature. While Indigenous peoples lived in the area for more than 10,000 years, it was only in the late nineteenth century that the United States formally began studying the area.

In 1872, Congress approved the establishment of the national park, thanks in part to Thomas Moran’s artistic renderings, which carried Yellowstone’s dramatic beauty all the way to legislators in the east. Because of that, visitors today can experience the 2.2 million acres, and its animals, in much the same way Mr. Moran did.

If that sounds like a lot of ground, hold onto your hats, folks, because the park sits in the middle of the 12 million-acre Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. It’s big enough to give animals the space they need to graze, hunt, and live as they have for thousands of years—and it gives us binocular-wielding enthusiasts the space we need to admire them from a safe distance.

Prepping, Packing and Planning for Your Wildlife Tour in Yellowstone

The park is huge, and that’s both the allure of a stateside safari, and one of the challenges. For a wildelife watching trip in Yellowstone, know it’s not a crapshoot that comes down to dumb luck—you can actively plan to be in the right place at the right time. A guide with local ecological knowledge can help to increase your chances of seeing the animals you’re most interested in, including wolves and grizzlies.

When you do visit, you’ll want to make sure you have all the right gear to keep you safe and comfortable.

In the summer, temperatures can swing from freezing to 85°F (29°C) in a single day, with thunderstorms and blue-bird skies thrown in for good measure. In the winter, it can get as low as -40°F (-40°C), and just because the sun is out doesn’t mean you’ll feel its warmth.

With that said, most people come in the summer and early fall, so you’ll want to bring plenty of layers and rain gear, appropriate footwear, a water bottle or two, and a good hat.

Oh, and lots of sunscreen. We’re at a high base elevation (about 5,000 feet) and often go over 9,000 ft in the course of the day. I’ll tell you what—I’ve earned each and every one of my wrinkles getting blasted by those UV rays.

If you’re sensitive to bug bites, I suggest wearing loose clothing that covers the lengths of your arms and legs. That’ll reduce the amount of bug repellent you’ll want to use, which is a good thing for the insects that are so critical to the greater ecosystem.

To help you plan your own trip, below is a sample itinerary covering three main sights. But, the beautiful thing about national parks is that you have the freedom to shape your experience—so feel free to use this as a starting point and strike out on your own.

How to Spend Three Days in Yellowstone: The Best Places to See Wildlife

Day One: Photograph the classics

The Northern Range and Lamar Valley are the crème de la crème of wildlife watching in Yellowstone, where herd paths wind for miles and wildflower blooms are a thing to behold. You are likely to see pronghorn and bison among the blooms—a picture-perfect view.

Speaking of which, Yellowstone is a photographer’s dreamscape. If you have a long lens, you’ll be able to capture details down to the talons of golden eagles and the plumes of a trumpeter swan. No worries if you don’t have that kind of gear—guide outfits, like ours, may have spotting scopes (Swarovski are the best!) that allow everyone to see these denizens in detail from afar.

Sometimes, those details are crucial for identifying what it is exactly you’re looking at. For example, black bears, despite their name, can sometimes be cinnamon-colored, deceptively making them appear to be grizzly bears. What you really need to look out for, more than the color, is the bump on the bear’s shoulders. Remember: if that hump is larger than the rump, it’s grizzly.

Day Two: Gorging on Geology

Many people don’t realize this, but Yellowstone actually sits atop a supervolcano—which fills the park with geological features like hot springs, geysers, and canyons.

Approximately 630,000 years ago, a volcanic eruption caused the land to sink in on itself, creating a caldera that spans more than 1,500 square miles. Across the park, there are more than 10,000 hydrothermal features, so it’s no surprise that the Apsáalooke people, often referred to as Crow in English, named the area the land of steam.

In Mammoth Hot Springs, warm groundwater drives up through an ancient limestone layer, pushing calcium to the surface and forming beautiful terraces. You’ll see features that tell the stories of ancient seas that have long since dried up, volcanoes and their explosive history, and life at the microbial level.

Another renowned geological feature is Yellowstone’s very own Grand Canyon. (It’s like experiencing two national parks for the price of one!). Walking the rim, you’ll see the colors that so inspired Thomas Moran.

Does Old Faithful ring a bell? She’s probably the nation’s most iconic geyser. If you’ve never been to the park, any talk of geysers or geothermal features may dredge up some vague memories from a high school earth science class. For those of you who may need a refresher, these springs form when geothermally heated groundwater leaks—or erupts—from the earth’s surface. The water can also collect in beautiful jewel-colored pools.

While Old Faithful may be the A-List celebrity of the geyser world, Norris Geyser Basin claims the title of oldest geyser basin in the park. If luck is on our side as we walk around the basin, you could see the recently-active Steamboat show why it’s the tallest geyser in the world.

While these popular geysers are well marked and fenced-off, it’s important to remember that there are geothermal features well off the beaten track too. So for all you hikers and backpackers, there are plenty of day hikes that help you see the most impressive scenery of Yellowstone, just be cognizant of where you step as you enjoy the backcountry.

Day Three: A river runs through it

It’s important to remember that people walked Yellowstone’s meadows and mountains long before the United States Government sent out expeditions to the region. Indigenous groups

Have lived in the area for more than 10,000 years, and there are 27 tribes affiliated with the land. One of my favorite parts of celebrating the park’s 150th birthday was gathering with members of the Indigenous tribes whose families have been here for generations, and I’m always grateful for the opportunities to connect and learn from them.

The park’s name has its roots in Hidatsa, an Indigenous language. The Yellowstone River—which happens to be one of the park’s best places to see eagles, osprey, kingfishers and song birds—cuts nearly 700 miles across Montanna. The Minnetaree Indigenous people originally named the river Mi tse ad-iz-i, meaning “the yellow rock river” because of the yellow sandstone in the area. When French fur trappers arrived, they translated the name to Roche Jaune, which becomes “Yellowstone” in English. As one of the last undammed rivers in the United States, the Yellowstone River is wild in and of its own right.

Tips for Wildlife Observation in Yellowstone Park

The best time to see wildlife in Yellowstone

There are a few things you need to take into account when planning your trip: what animals you want to see, when you want to be in the park, and how you want to experience the landscape.

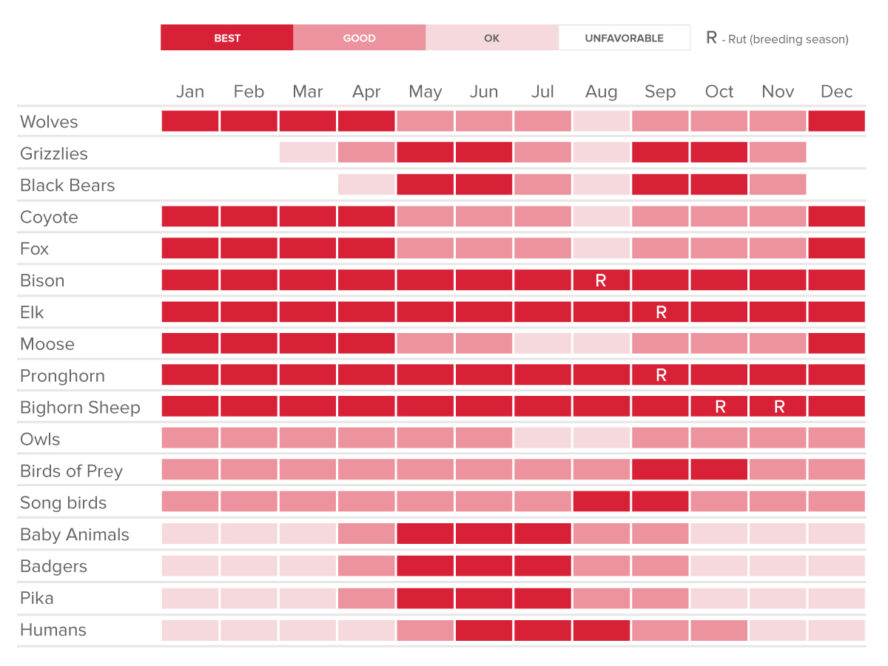

Once you know what animals you’d like to see, you can use that to inform your decision about what time of year to go to the park. For example, the grizzlies and black bears will be hibernating in the winter, so if you’re hoping to catch a glimpse of those guys, you’ll have the best luck between May and October. Late spring and early summer is also the best time to see song birds, badgers, and baby animals.

Moose come down into the valley in winter, so that’s a good time to catch them. Another winter bonus: you can see cute little otter tracks in the snow where they’ve gilded around on their bellies.

For some animals, like bison, elk, and bighorn sheep, you’ve basically got an equally good chance of seeing them any time of year. So if the kind of wildlife you want to see doesn’t help inform when to visit the park, there’s some other fauna to keep in mind: humans.

Yellowstone hosts more than 4 million visitors each year, with peak season being June through September. If you don’t love crowds, you might want to consider visiting in the winter. That’s not to say if you do visit in the summer you’ll be walking the trails conga-line style. Remember, the park spans more than 2 million acres, so if you’re up for hiking in the backcountry you’ll be able to put some space between yourself and other visitors.

Which brings me to my third point—think about how you want to experience the park. Hiking and wildlife observation go hand-in-hand. Hike out to the hills to see the bighorn sheep, out to the meadows for the grizzlies. You can still hike in the winter, but your options expand to include skiing and snowshoeing. Even just driving along the 200 miles of the park’s roads offers potential for spotting wildlife, but be extra careful and mindful of other drivers.

Be respectful and stay safe

I get it—bison can be cute. Coyotes too, and bears and foxes and marmots. But despite their endearing little noses and fluffy coats, it’s absolutely critical—for both your safety and theirs—that you not try to pet them.

In fact, if you’re close enough for petting to even be a possibility, you are far too close. For larger animals like bears and wolves, you need to stay at least 100 yards away. For other animals, keep it at least 25 yards. And that’s the minimum—if you can tell the wildlife is changing its behavior because of your presence, it’s on you to increase your distance or leave all together. Remember, this is their home.

Other rules for safe observation on the trails are in line with just about any other outdoor activity—pack-in-pack-out and let people know where you’re going and when to expect you back. And if you’re driving through the park, be cognizant of other drivers and do not stop in the middle of the road to take a gander at nearby wildlife. But—it should probably go without saying—certainly DO stop to allow wildlife to cross the road.

Just another day in Yellowstone

I’ve been here almost eight years, and I always find a new experience during my treks across Hayden Valley. Just the other day, I watched a wolf feed on a carcass down by the river. I turned 180 and saw bison grazing as a bald eagle soared overhead. I heard grunts, snorts, piercing calls and hoots, all intermingled with the sounds of a brook nearby and wind through the grass—a wild space, truly.

Ready to observe the best wildlife that Yellowstone has to offer (respectfully, of course)? Watch Cara’s webinar to learn more or sign up for a tour today!